|

Plasma

The Electric Universe

It's Electric

Electric Weather

EDM

EU Geology

Electric Comets

Further

Science and Philosophy

Ancient Testimony

Cutting Edge

The Way Forward

Latest News

Video

|

|

|

|

|

"We are trying to prove ourselves wrong as quickly as possible, because only in that way can we find progress." Richard P. Feynman

|

|

|

| | | |

| Electric Comets |

|

|

| | | |

|

Comets are often described as the Rosetta Stone of the Solar System — relics from its formation that should, in principle, be well understood. Instead, they have become a persistent problem for the standard model. A growing catalogue of observations — from unexpected jet behaviour and activity far from the Sun to abrupt outbursts and finely structured plumes — sits uneasily with the traditional dirty snowball narrative.

Plasma Cosmology and the Electric Universe begin from a different premise. Space is not an electrically neutral vacuum, and a comet is not merely a passive lump of ice warming and evaporating or sublimating. It is a body moving through a plasma environment, capable of electrical interaction, surface charging, and discharge phenomena.

For a primer video, see Thunderbolts Project:

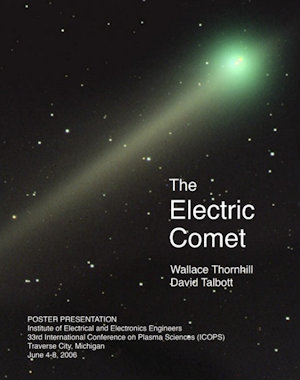

The Electric Comet |

|

|

| | | |

| The Failed Dirty Snowball Hypothesis |

|

|

| | | |

|

Conventional astronomy has long treated comets as icy relics whose activity is driven primarily by solar heating. Ices sublimate, gas drags dust into a coma and tail, and activity should fall away as volatiles are exhausted.

Yet repeated observations complicate the story: unexpected jet behaviour, activity far from the Sun, abrupt outbursts, sharp surface features, and emissions at energies not easily reduced to simple heating. The dirty snowball model has often required additional patches added after the fact.

A model that must be repeatedly rescued by special pleading is not a model at rest.

|

|

|

| | | |

| Electric Comets in a Plasma Environment |

|

|

| | | |

|

The Electric Universe view begins with a straightforward premise. If space is a plasma, then bodies moving through it can exchange charge. Electrical stress can drive surface discharge, sputtering, and excavation, producing jets, coma formation, and tail structure without requiring a fragile ice body to behave like a perfect thermostat.

In this view, a comet's coma is not merely gas from melting ice, but a plasma sheath interacting with the Sun's electrical environment. As discharge regimes intensify, one expects rapid brightening, filamentary jets, and abrupt changes in activity.

|

|

|

| | | |

| 3I/ATLAS and Electric Comet Confirmations |

|

|

| | | |

|

In recent years, the discovery of interstellar visitors — alongside a steady stream of “anomalous” comet behaviour closer to home — has revived public interest in a question that orthodox models rarely treat as urgent: what actually drives comet activity? When an object displays sustained activity that doesn’t scale neatly with solar heating, the conversation tends to split into two familiar camps.

One response is to patch the dirty snowball model: add hidden reservoirs, exotic volatiles, “freshly exposed ice,” rotational tricks, unusual thermal conductivity, or other special circumstances that preserve the core assumption (heating ? sublimation ? jets). The other response is to consider a different physical premise altogether: a comet as an electrically active body moving through a plasma environment, capable of charge exchange, sheath formation, and discharge phenomena.

From an Electric Universe / plasma perspective, several “surprises” look less like surprises. Sunward-directed plumes, for example — so often treated as puzzling through a purely thermal lens — fit neatly with an electrical interaction model. In a plasma environment, filamentary jets, abrupt outbursts, sharp collimation, and rapid changes in activity are not automatically reduced to “ice behaving badly”; they can be interpreted as signatures of energetic interaction between the object and its surrounding plasma, where discharge regimes can intensify or relax quickly as conditions change.

In other words: if the mainstream model repeatedly requires emergency add-ons, while the plasma/electrical framework anticipates the class of behaviours being observed — including structured, sometimes sunward plumes — then it’s worth asking which premise is doing the real explanatory work.

For readers who want a deeper dive, I have narrated two dedicated video analyses of Comet 3I/ATLAS — one for the Thunderbolts Project, and one for my own channel, Dissonant Dragon.

|

|

|

| | | |

| UFOs, Failed Predictions, and Deflection |

|

|

| | | |

|

Whenever a comet or visitor object behaves "wrong," a predictable cultural detour often follows: speculation about alien craft. Whatever one's views on UFOs as a broader topic, in the comet context it frequently functions as a convenient distraction. The public argument shifts from "Why did the model fail again?" to "Could it be intelligence?" — and the foundational scientific question quietly slips off the table.

But the scientifically interesting issue remains the same, and it's far more testable: why do standard assumptions keep colliding with repeat anomalies? When the unexpected becomes routine — sunward jets, sudden outbursts, filamentary structures, non-thermal emissions, activity that doesn't "behave" with distance the way it's supposed to — the honest response is not to change the subject. It is to re-examine the premise.

The point isn't to demand agreement. It's to demand clarity: are we watching nature misbehave — or are we watching a model persist past its sell-by date?

|

|

|

| | | |

| Radio Signals and the Alien Reflex |

|

|

| | | |

|

Another recurring trigger for extraterrestrial speculation is the detection of unusual radio emissions — signals that are quickly framed, in some quarters, as possible evidence of technology.

This reaction is nothing new. Structured or repeating radio signals have a long history of being misinterpreted, despite the fact that plasma interactions routinely generate radio-frequency emissions. The Sun does it. Planets do it. Comets do it. Any charged body moving through a plasma environment can do it.

Electrical discharges, current filaments, plasma boundaries, and interactions with the solar wind naturally produce radio emissions that can appear coherent, intermittent, or even artificial to an observer expecting purely thermal behaviour.

Once again, the simplest explanation is overlooked: not alien transmitters, but electromagnetic and plasma effects — effects that remain underplayed largely because electrical interactions are still treated as secondary within a gravity-only, sublimation-first framework.

|

|

|

| | | |

| Seven Jets, One Rotating Nucleus — a Plasma Signature |

|

|

| | | |

|

One of the most discussed features of 3I/ATLAS has been the appearance of multiple discrete jets — seven, by some counts — emerging from a nucleus that appears to be rotating, while the jets themselves refuse to behave as rotating features.

This is already a problem for the standard model. In the thermal venting framework, jets are treated as miniature thrusters: sunlight warms surface ice, gas escapes, dust is dragged along, and activity rises and falls as illumination changes.

If that were the whole story, the geometry should be straightforward. Thermal jets should be:

- tightly tied to sunlit regions,

- strongly modulated by rotation,

- and transient as illumination changes.

Instead, the jet geometry can become oddly stable. Jets persist when they "shouldn't." They maintain structure despite changing illumination. They look organised — filamentary — and this is precisely why some observers leap to the wrong conclusion: "That looks engineered."

But this is precisely where the electrical interpretation becomes more intuitive. In a plasma environment, a comet is not merely shedding gas — it is an electrically immersed body, surrounded by a plasma sheath, moving through regions of changing electric potential. What we see are not simply vents, but discharge structures.

Electrical activity does not have to spin with the nucleus. It does not have to follow the Sun like a spotlight. Discharge tends to:

- anchor to electric field gradients,

- align with current paths,

- and concentrate in preferred regions dictated by plasma conditions, not sunlight alone.

A simple analogy makes this intuitive. Take a high-street plasma globe and place your fingers on opposite sides. You can rotate the glass all you like — but the luminous filaments will, for the most part, remain fixed toward the electrical differential created by your touch. The structure responds to fields, not to the motion of the container.

So multiple jets, unusual stability, and poor correlation with rotation are not anomalies that strengthen the "alien craft" narrative. They are exactly the kind of behaviour one expects when a body is immersed in, and responding to, a changing plasma environment.

Not boiling. Not venting. Structured discharge.

|

|

|

| | | |

| Wal Thornhill and Comet Tempel 1 |

|

|

| | | |

|

The Tempel 1/Deep Impact mission offered a rare and revealing opportunity: a deliberately engineered impact into a comet nucleus, observed before, during, and after the event. The mission was widely framed as a direct test of the dirty snowball model, with expectations rooted firmly in sublimation-driven behaviour and a mechanically weak, icy surface.

Prior to the encounter, Wal Thornhill — approaching comets through the Electric Universe framework — issued several specific, testable predictions that departed sharply from the mainstream narrative. He argued that the resulting crater would be far smaller than anticipated, that the event would be dominated by dust rather than exposed ice, and that a brief but intense flash would occur before the projectile physically struck the surface — consistent with an electrical discharge rather than a purely mechanical collision.

When Deep Impact unfolded, these expectations were borne out in ways that surprised mission scientists. The anticipated large, clean crater failed to materialise, dust production overwhelmed optical measurements, and a luminous flash preceded contact. During the live broadcast, one NASA scientist was heard to remark, candidly, “I’m at a loss to explain it…”

Matt Finn revisits these events in the Thunderbolts Project episode Set the Record Straight, documenting how Deep Impact inadvertently validated key elements of the Electric Comet model — not through reinterpretation after the fact, but through predictions made in advance.

“All the things we see around comets fit the electrical model but don’t make much sense in terms of icy snowballs sublimating into space.”

Wal Thornhill

“It is surprising that they continue to be surprised by all the surprises.”

Wal Thornhill

Predictions made in advance matter. They allow observers to distinguish between a model that explains observations only after the fact, and one with genuine forecasting power. In that respect, Deep Impact was less a refutation of the Electric Comet hypothesis than an unplanned stress test — one that exposed the growing gap between expectation and observation in conventional comet theory.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Debunking as Theatre |

|

|

| | | |

|

As the Electric Comet model gains traction, it tends to attract a familiar response — not a careful audit of the data, but debunking videos aimed at shaping public perception. One widely circulated example is a video by science YouTuber Dave Farina, who presents himself under the moniker “Professor Dave” while arguing that the Electric Comet idea has been decisively refuted:

Wal Thornhill Is a Complete Fraud (Thunderbolts Project Debunked).

At approximately 10:45 in the video (645 seconds), the argument turns on a specific claim: that magnetometers aboard Rosetta and Philae would have detected any meaningful electrical activity at the comet, and that their failure to do so constitutes a decisive “death blow” to the Electric Comet hypothesis.

Here is the claim, in Professor Dave's own words:

“…the centerpiece of Wal’s three-ring circus, the electricity. There wasn’t any. As with all previous comet missions, both Rosetta and Philae were fitted with magnetometers. Those instruments would detect any electrical discharge with ease. They didn’t detect any. If you are going to pretend that comets are electric, and a craft physically lands on one and doesn’t detect any electricity, that’s what’s called a death blow.”

The difficulty is not rhetorical, but instrumental. A magnetometer measures magnetic field vectors. It does not directly measure electric fields, charge separation, surface charging, plasma sheaths, ion pick-up, or double layers. Expecting a magnetometer to register such phenomena is a category error — akin to expecting a thermometer to measure wind speed. This is a classic example of the Dunning-Kruger effect in action.

Rosetta’s magnetometer results were important and informative. They demonstrated the absence of a permanent, nucleus-wide magnetic dipole at comet 67P. They did not demonstrate the absence of plasma interaction, electrical stress, or current-driven phenomena — many of which were documented by Rosetta’s plasma and particle instruments.

Titles aside, this section does not ask the reader to take sides. It asks for something simpler and more fundamental: to distinguish instruments by what they actually measure, and to distinguish genuine prediction from post hoc storytelling.

|

|

|

| | | |

| A Wider Issue: Framework Protection |

|

|

| | | |

|

There is also a broader philosophical point about how debunking culture frames science. In one interview, Jim Baggott summarises the priority as:

"Your mission is to get the maths to work out correctly. That's your first priority. Get the maths to work in a way that's consistent with theoretical structures that have gone before, and hopefully in such a way that might give you some insights as to an experimental test."

If the first obligation is to preserve prior theoretical structures, mathematics becomes the master and observation the servant. That is not skepticism. It is framework protection.

Instruments matter. Predictions matter. When a decisive claim hinges on misunderstanding what an instrument can and cannot measure, the debunk collapses under its own certainty.

|

|

|

| | | |

| References: Instruments and Rosetta Findings |

|

|

| | | |

|

This section exists for one specific reason: to remove any ambiguity about what Rosetta’s magnetometer measurements can and cannot be used to claim. Much of the popular debunking rhetoric surrounding electric comets — including Professor Dave’s “death blow” argument — hinges on a fundamental misunderstanding of instrumentation.

The claim is simple and rhetorically powerful: if comets were electrically active, Rosetta’s magnetometers would have detected this directly. They did not. Therefore, the electric comet model is refuted.

The problem is that this conclusion does not follow from the premise. Magnetometers do not measure “electricity” in the general sense invoked by such claims. They measure magnetic field vectors. They do not directly detect electric fields, charge separation, plasma sheaths, surface charging, ion pick-up, or double layers. Conflating these categories turns a precise instrument into a catch-all sensor it was never designed to be.

I. What Magnetometers Do — and Do Not — Measure

-

Jacobs, J. A. (1970), Magnetometers for Space Research, Space Science Reviews.

A foundational review still used in space-physics training. It carefully distinguishes between intrinsic magnetic fields, magnetic fields generated by plasma currents, and phenomena magnetometers cannot detect at all — including electric fields, surface charging, plasma sheaths, and double layers.

ADS abstract

-

Precision Magnetometers for Aerospace Applications (Sensors, 2021).

A modern technical overview of spaceborne magnetometers, explicitly stating that these instruments measure magnetic field vectors only. They do not measure charge distributions, electric potentials, or plasma boundary structures.

NCBI / PMC link

These papers establish a baseline that is rarely acknowledged in popular debunking videos: magnetometers are not general “electricity detectors.” Expecting them to register surface charging or plasma sheaths is a category error.

II. Rosetta Found No Intrinsic Dipole — Exactly as Expected

-

Goetz et al. (2016), First detection of a diamagnetic cavity at comet 67P, Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Rosetta detected a field-free (diamagnetic) cavity near the nucleus, demonstrating that magnetic fields were excluded by plasma currents — not absent because no interaction was occurring.

A&A link

-

Goetz et al. (2016), Structure and evolution of the diamagnetic cavity, MNRAS.

Shows how current systems and plasma flow shape the magnetic environment around the nucleus, producing near-zero field regions measurable by magnetometers.

MNRAS link

In other words, Rosetta’s magnetometer results did not demonstrate the absence of plasma or electromagnetic interaction. They demonstrated the absence of a permanent, nucleus-wide magnetic dipole — a result nobody on the electric comet side predicted or required.

III. Plasma Interaction Was Detected — By the Appropriate Instruments

-

Spatial distribution of low-energy plasma around comet 67P (arXiv).

Documents structured plasma populations close to the nucleus using Rosetta’s plasma instruments.

arXiv link

-

Electric field emissions at the plasma frequency near comet 67P, Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Reports plasma wave and electric field phenomena measured in situ — precisely the kind of interaction magnetometers are not designed to detect directly.

A&A link

-

Koenders et al. (2016), Hall effect in the coma of 67P, MNRAS.

Models and confirms current sheets and induced magnetic structures driven by plasma flow, not intrinsic magnetism.

arXiv link

These observations are entirely consistent with a comet immersed in — and interacting with — a plasma environment. They do not require the nucleus itself to be magnetised, nor do they require magnetometers to register large-scale discharge signatures.

IV. Surface Charging and Plasma Boundaries

-

Deca et al. (2017), Surface charging and emission of comet 67P, Physical Review Letters.

Combines Rosetta data with particle-in-cell simulations to demonstrate surface charging, plasma sheaths, and electrostatic boundaries — phenomena invisible to magnetometers by design.

APS link

The takeaway is straightforward. Rosetta’s magnetometer did exactly what it was designed to do — and its results are often misused by commentators who blur the distinction between magnetic fields and electrical phenomena. When the correct instruments are considered, Rosetta’s findings are not a refutation of plasma-electric interaction, but evidence of it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|